If your feet hurt, you’re not alone. Around 75% of people will face a serious foot problem at some point in their lives. But here’s what most people don’t know: foot pain usually doesn’t start with your feet. It starts with what you wear on them.

Shoes are not just fashion. They are tools that affect how your body works. Bad shoes can cause pain in your ankles, knees, hips, back, and neck. Good shoes, on the other hand, can prevent that chain reaction. That’s where orthopedic shoes come in.

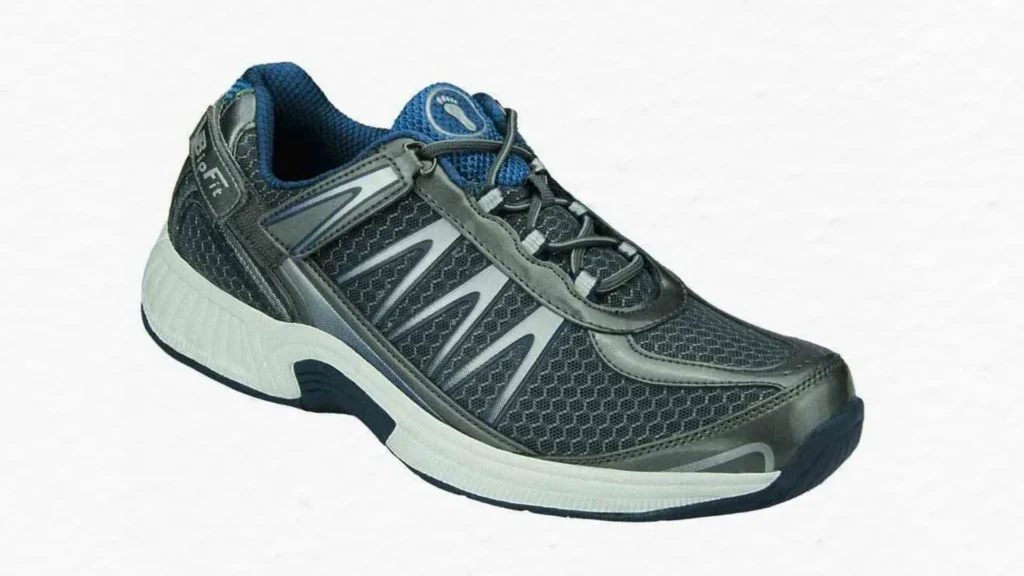

Orthopedic shoes are designed to fix problems, not cause them. They support the way your body was built to move. And every small design choice—every curve, material, or angle—has a purpose backed by science.

In this article, you’ll see how orthopedic shoes are built, why each feature matters, and how the right design can reduce pain, improve posture, and change how you move through the world.

The Foot Isn’t Simple—and Neither Are Its Problems

Your foot has 26 bones, 33 joints, and over 100 muscles, ligaments, and tendons. That’s more moving parts than your hand. All of these work together each time you take a step. But that system breaks down when something is off.

Some feet are flat. Some are high-arched. Some roll in too far when walking. Some don’t roll in enough. These small differences are called biomechanical faults. They don’t always hurt at first. But over time, they can lead to pain in places that don’t seem related.

Orthopedic shoe designers use motion studies to understand these faults. With tools like pressure scanners and 3D gait analysis, they track how the foot moves, where pressure builds up, and how a person’s body shifts with each step.

The goal isn’t just to cushion the foot. It’s to correct the way the foot works, starting from the ground up. And that begins with five things: the last, the arch, the sole, the heel, and the toe box.

The Five Pillars of Good Orthopedic Design

Orthopedic shoe design is not built on guesswork or trends. It’s built on five key components that all serve one goal: to support natural movement and reduce stress on the body. Every part plays a role. Get one wrong, and the entire system starts to break down. But when all five are right, the results can be life-changing.

1. The Last: Where Fit Begins

The “last” is the base form that every shoe is built around. Think of it as the shoe’s skeleton. Most regular shoes use a single standard last to fit millions of people. But everyone’s feet are different. That one-size-fits-all approach doesn’t work.

Orthopedic designers don’t use random shapes. They scan thousands of real feet from different age groups, weight ranges, and foot types—flat feet, high arches, wide forefeet, narrow heels, and more. From that data, they build a full range of lasts that reflect the actual variety of human feet.

The more precise the last, the more natural the fit. A good orthopedic last prevents the foot from sliding forward, squeezing at the sides, or lifting at the heel. That’s critical. When a shoe holds your foot in the right place, you reduce hotspots, pressure points, and fatigue.

Some brands go further. They create gender-specific lasts, since men’s and women’s foot shapes differ not just in size, but in proportion. Others make lasts that mimic natural walking angles, rather than forcing the foot into a flat base. The goal is to help the shoe support your foot’s shape—not reshape your foot to match a flawed shoe.

2. The Arch Support: Your Body’s Shock Absorber

The arch is the foot’s built-in spring system. When you walk or run, it flattens slightly to absorb force, then lifts to push your body forward. That motion is vital for balance, energy transfer, and joint protection.

But if your arch is too low or too stiff, that motion gets blocked. Your body finds workarounds. Your knees twist. Your hips overcompensate. Your back absorbs more shock. That’s where problems begin.

Orthopedic shoe makers solve this with targeted arch support. They don’t rely on guesswork or soft padding. They study the arch’s height, length, and position during movement. Then they build support that matches those measurements exactly.

Materials matter. Memory foam feels soft, but often flattens too quickly. EVA (ethylene vinyl acetate) is more stable and lasts longer. Dual-density foams—firmer in the arch and softer in the heel—balance both comfort and control. Some high-end shoes even use custom-fit thermoplastics that mold to the foot with heat.

Good arch support does more than ease pain. It trains the foot to move better. Over time, that reduces fatigue, improves balance, and helps correct alignment across your entire body. It also helps people with common conditions like plantar fasciitis, flat feet, and arthritis walk longer without discomfort.

3. The Sole: A Smart Foundation

The sole may seem simple. It’s the bottom of the shoe. But for orthopedic design, it’s one of the most engineered parts.

A quality orthopedic sole has to do three things: absorb shock, guide motion, and maintain stability. But it can’t do all of these at once in the same spot. That’s why orthopedic soles are divided into zones—different parts with different jobs.

The heel zone uses high-density foam or rubber to soften impact when your heel strikes the ground. This protects your knees and spine. The midfoot zone is firmer, giving you support as your weight shifts forward. The forefoot is more flexible, allowing your toes to bend naturally as you push off.

One common orthopedic feature is the rocker sole. It’s a curved shape that helps your foot roll forward more smoothly. This is especially useful for people with stiff joints, weak toe movement, or foot drop. It reduces the need for muscle control in every step, which makes walking less tiring.

Sole materials vary by purpose. Some are rubber-heavy for durability. Others use TPU (thermoplastic polyurethane) for better traction and energy return. Designers also test soles on different surfaces—wet floors, uneven trails, indoor tiles—to reduce slips and falls. The right sole grips when needed but still flexes at the right angles.

A flat sole or cheap foam may feel soft for a week. But over time, it compresses and warps, leading to loss of support. Orthopedic shoes prevent that with reinforced midsoles, firm shanks, or carbon plates that hold their shape through thousands of steps.

4. The Heel Counter: Small Part, Big Role

The heel counter is the back portion of the shoe that wraps around your heel. It looks simple but plays a major role in keeping your stride stable.

Your heel controls the first contact with the ground. If it wobbles or tilts, your whole leg alignment changes. That leads to twisting at the knee and stress at the hip. A strong heel counter keeps that motion in check.

Orthopedic heel counters are usually made from TPU or thermoplastic. They are shaped to cup the heel snugly without pressing too hard. Padding adds comfort while preventing slippage. Some designs rise slightly higher on the ankle for added control, especially for people with balance issues or weak ankle muscles.

This part of the shoe also helps manage pronation (rolling inward) and supination (rolling outward). Both can be harmful if left unchecked. By guiding the heel into a more neutral landing, the heel counter helps protect the knees, hips, and lower back from extra strain.

In people with Achilles tendon issues or plantar fasciitis, a firm heel counter can reduce strain on the tendon by limiting side movement. That means less inflammation, fewer flare-ups, and better long-term healing.

If your heel doesn’t stay centered during walking, you’re wasting energy with every step. A proper heel counter prevents that.

5. The Toe Box: Space That Saves

Your toes play a bigger role in balance than most people think. When they’re cramped, you lose stability, grip, and push-off strength. That’s why the toe box—the front part of the shoe—must be built for room and function, not just looks.

Most regular shoes taper at the front, forcing the toes into a narrow space. This can cause bunions, hammertoes, and nerve pain. It can also change the way you walk, as your foot shifts to avoid pressure.

Orthopedic shoes fix this with wider and deeper toe boxes. They follow the natural shape of your forefoot—not a designer trend. Your toes should be able to spread out and lie flat, with at least half an inch of space in front.

For people with conditions like Morton’s neuroma, hammertoes, or swollen joints, a flexible toe box is critical. Some shoes use mesh that stretches with the foot. Others use seamless interiors to avoid friction that can lead to blisters or wounds.

Designers test these shapes using pressure maps. They place sensors across the toes and forefoot, then watch how pressure changes during walking. If one spot gets too much force, they go back and adjust the design.

Toe space is also key for people with diabetes, who may lose sensation in the feet. A tight toe box increases the risk of ulcers, which can become serious if left untreated. A good orthopedic shoe avoids that by offering both space and protection—no sharp seams, no rigid bumpers.

Room in the front of the shoe doesn’t mean sloppy fit. It means functional design. And in orthopedic science, that’s the difference between pain and relief.

How Data and Testing Shape Every Design

Orthopedic shoe design isn’t guesswork. It’s tested in labs and clinics.

Designers work with podiatrists, physical therapists, and engineers. They collect real-world data—pressure points, balance shifts, and muscle fatigue. This feedback loop helps fine-tune every part of the shoe.

Some companies use force plates. Others use infrared tracking or in-shoe sensors. They measure how a person walks before and after using the shoe. They record changes in step length, foot speed, and joint angle.

This isn’t just for athletes. It helps seniors avoid falls. It helps diabetics avoid ulcers. It helps workers stay on their feet without pain. And the difference can be felt after just one day of proper wear.

Orthopedic shoes reduce pain. That’s the goal. But that’s only the beginning.

- They Improve Posture. When your feet are aligned, your spine lines up better. You stand straighter without effort. This reduces back and neck strain over time.

- They Lower Injury Risk. Stable shoes mean fewer twisted ankles, fewer stress injuries, and less wear on joints. People who wear them report fewer overuse problems.

- They Increase Energy. When your feet don’t hurt, you walk more. Your muscles work less to keep you balanced. You get tired less quickly. Small gains add up each day.

- They Delay Surgery. Many foot surgeries can be avoided or delayed if biomechanical faults are corrected early. Orthopedic shoes are part of a non-invasive solution.

- They Support Special Conditions. For people with diabetes, arthritis, or neuropathy, orthopedic shoes are not optional. They help prevent wounds, reduce swelling, and improve circulation.

And they aren’t ugly anymore. Advances in material design and 3D knitting allow orthopedic shoes to look like regular sneakers or dress shoes—without losing function.

Orthopedic shoes are not magic. They’re tools built from years of testing, study, and patient feedback. Every curve has a reason. Every material has a role.

They support the way your body moves. They correct small faults before they become big problems. And they turn walking from a painful task into a natural, smooth experience.

So if your feet hurt—or if you just want to move better—the answer may not be new pills or physical therapy. It may be something much simpler: better shoes, built with science.